If we dig deep into data sources from the National Center for Education Statistics, we’ll find table number 325.35. There, we can see some interesting figures regarding the number of degrees in computer and information science from 1970 to 2017 according to level of degree and sex. If we plot the percentage of women Bachelors through the years we get to the really compelling facts: the curve starts going up from 1970 at 13% and peaks at 37% in 1984. But what’s much more interesting is that from there, it goes down, with a 10-year stable period up until 2003, after which, it keeps going down until we get to today’s stats at 20%, not much higher than when it started. This is even more evident when we compare it with other majors.

Why did women stop coding?

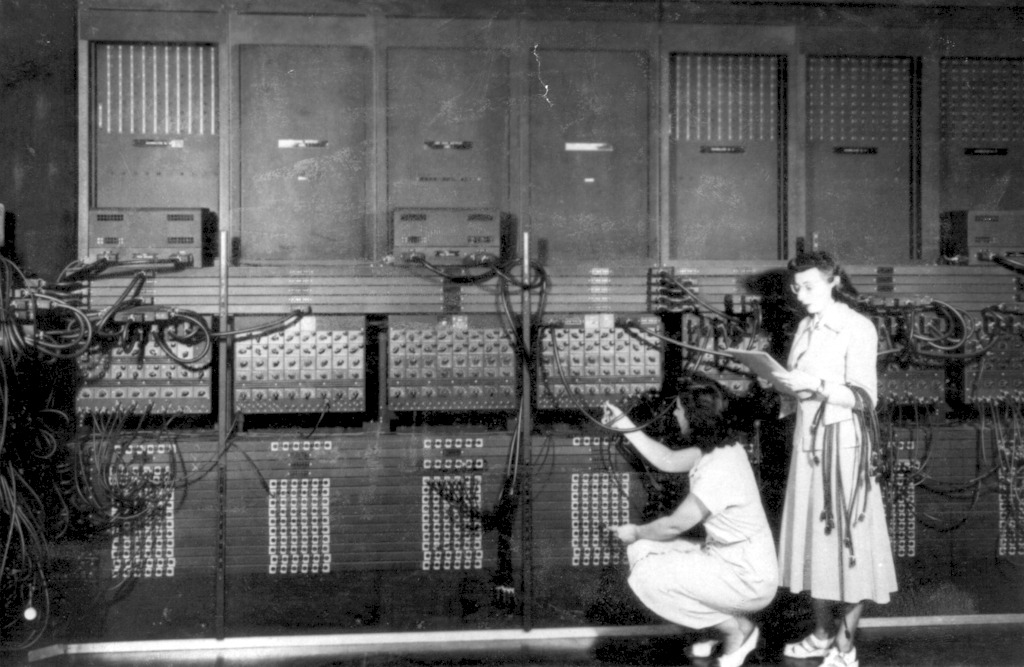

So, what happened after the peak? At the dawn of our field, computer programming was regarded as women’s work. During World War II, the military hired hundreds of women to compute and improve the accuracy of the Allies’ attacks. A group of six women, often referred to as Top Secret Rosies, were recruited by the army to program the ENIAC (the first general-purpose digital computer) for this objective. Their work was hidden to the point where, when images of them were released next to the computer, they were described as models.

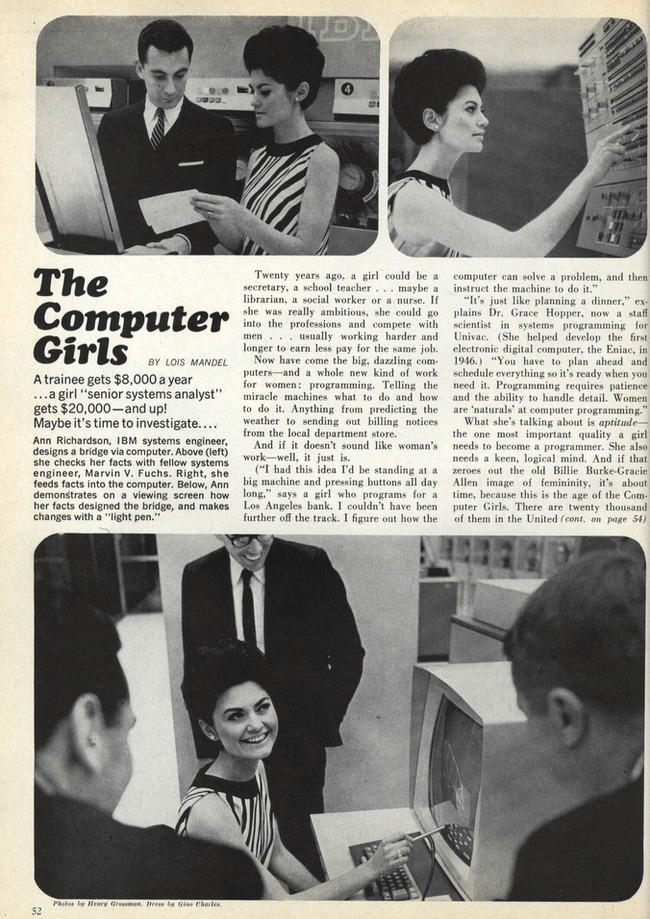

Men specialized in hardware while software development was seen as an exciting alternative to secretarial work. In 1967, Cosmopolitan published an article titled The Computer Girls, encouraging young women to pursue careers in computer science. So the curve went up, and continued to do so up until 1984. That’s when personal computers appeared.

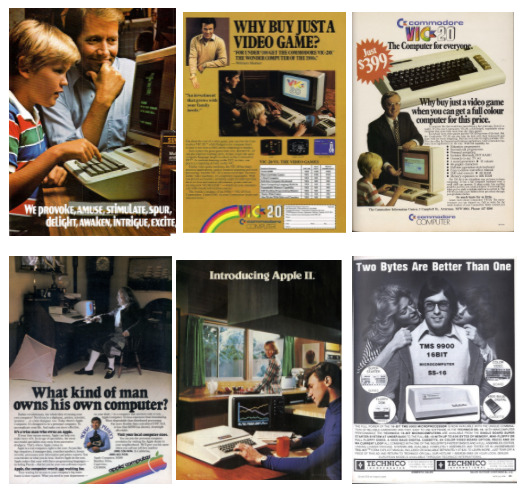

When Apple released the Macintosh 128K and the Commodore 64 was introduced to the market, they were presented as toys. And, as toys were gendered, they were targeted at boys. We can look at advertisements from that time and quickly find a pattern: fathers and sons, young men, even one where a man is being undressed by two women with the motto Two bytes are better than one. It’s more evident with the ads for computer games; if women appear, they do so sexualized and half-naked. Not that appealing for young girls, one could imagine.

This is also reflected in other consumer culture of that time; movies like War Games, Revenge of the Nerds and Weird Science all depict the same trope of the geeky male hero that saves the day and gets the girl. So, when the generation that grew up watching these stereotypes got to university, it’s understandable that not many young women could see themselves as computer scientists: they were never shown any.

This is replicated in a 1999 paper by Jane Margolis, Allan Fisher and Faye Miller called Caring about connections: gender and computing. They studied the perceived college environment at Carnegie Mellon by interviewing 51 women and 46 men majoring in CS. There, they found that the stereotypical “male-dominated hacker subculture” took a toll on those students that couldn’t identify themselves with that “intense, singular focus on computing and the computer itself”. As 44% of the women (compared to 9% of male students) reported that it was important for them to link their interest to computing to other arenas, they were hesitant to join this "computer science world" in which they sensed that the links to other interests in their lives would disappear. So many of them dropped out, and those that stayed in the program did so by finding a way to reconcile a “different” relationship to computing.

So, if we want a more inclusive field of work where everyone feels welcomed, it is time to think about the role models we present, and to consider that a different approach to computer science could be just as constructive and that much richer. Representation is key; you can’t be what you can’t see.